Wait 'till next year!, as they once said in Brooklyn.

Major League Baseball in 1918 found itself on the precipice of a change in epoch. In Cincinnati, the home of baseball's first all-professional team in 1869, the Reds were on the threshold of winning their first World Series (1919). The star player of those 1910s and 1920s Redleg teams was center fielder Edd Roush;

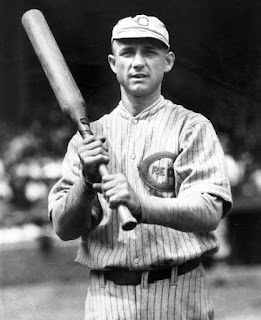

Photographed (above) in 1918, Edd Roush was the National League's best defensive center fielder in the 1910s and Roaring Twenties and in 1917 & 1919 the League's batting champion. In years that Edd was not the League batting champ, he batted; .333, .339, .352 in consecutive seasons, .351, .348, .339, .323. In his 17th and penultimate season, at the age of 36, Roush batted .324/.390/.451.

In a Cincinnati newspaper readership poll taken in 1950, Edd Roush was named the Reds greatest player for the first half of the 20th century.

Oddities far too numerous to address here (for example; position-specific player uniforms) abounded in 19th century baseball. Those antiquated anomalies faded as baseball drifted ever deeper into the 20th century in what long ago came to be understood as baseball's "modern era." Among the last of those now-strange oddities must surely have been Reds third baseman Heinie Groh (1914-1921) and his bottle bat (to say nothing of his 21st century snowflake triggering nickname);

Yes, that was a real baseball bat that Herr Groh swung regularly for many years. Game-used models of his bat may be found on display at the Reds Hall of Fame and at the Louisville Slugger Museum. As a Cincinnati Red, Groh once led the N.L. in hits, once in walks, twice in doubles and twice again in on-base percentage. Playing for the Redlegs, Heinie never swatted more than 5 home runs in a season and found himself utterly bereft of any such jacks in 1920. And also 1921. Such were the vagaries of playing in Major League Baseball's "Deadball Era."

The Deadball Era was a pitcher-dominated period. If the Washington Senators' Walter Johnson wasn't the best pitcher of the Deadball Era, it was the New York Giants' Christy Mathewson. Matty, aka "Big Six," pitched from 1900-1916 with the Giants. In July of 1916, and at the end of his playing days, Christy was traded from New York to the Cincinnati Reds (along with teammates Edd Roush and Bill McKechnie [later to gain fame as the manager for the 1940 World Champion Redlegs]). Mathewson pitched in just one game for the Reds, throwing a complete game, allowing 8 runs on 15 hits while striking out three and walking just one batter. Mathewson came to the Reds in that July 1916 trade to serve as player/manager for the Redlegs.

Christy Mathewson managed the Reds from 1916 through 1918. The photograph above was taken in 1918.

Competing for the crown of baseball's best pitcher in 1916-1917 (winning 23 and 24 games those two seasons, respectively) was a Boston pitcher that in 1918 was the individual who would almost single-handedly bring about the demise of the Deadball Era:

George Herman "Babe" Ruth (pictured here in 1918).

100 years ago this season saw Ruth record more than 300 plate appearances as a batter for the first time in his career. In ominous foreboding for the Deadball Era, Ruth led the American League in home runs in 1918 - his first time achieving this accomplishment - with 11 blasts. In 1919 the Babe repeated as the League's home run champ when he hit a then-record-breaking 29 home runs. In 1920 the Sultan swatted 54 homers and followed that record-breaking mark with a record-setting 59 bombs in 1921.

Babe Ruth circa 1918: Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for the Deadball Era.

Trivia; 1918 was the most recent season in which a pitcher started 15 or more games and also played 15 or more games in the field [Ruth].

Turning now to matters of a more parochial nature from 100 years ago.....

1917 saw a tornado rip through the tony Cincinnati neighborhood of Hyde Park;

Spanning the close of 1917 and the dawn of 1918, the mighty Ohio River was frozen over completely in Cincinnati;

The image above was photographed from a vantage point just about where you'll find the Reds' Great American Ball Park (and closer to where Riverfront Stadium stood once long ago), looking across the river to Covington, KY. On the south bank of the Ohio River, near the upper edge of the photo, you can see most of the (now, and then) old homes/mansions that are still present today along Covington's historic Riverside Dr. Back in the 1980s and 1990s Lou and I often parked (for free) on Riverside Dr and walked across the Roebling Suspension Bridge to Reds games, the span just out of view - at right - in the photo above.

My best guess is that you are looking, across the frozen Ohio, at Bellevue, KY and/or Dayton, KY in the photo above.

Closer again to downtown Cincy;

Well east of the Queen City, evidence (below) that the Ohio River was frozen solid for many miles;

In those days multitudes of steamships still navigated the Ohio and when the river froze over, many of those same steamers were trapped at Cincinnati. Eventually the weather warmed and brought with it not a slow, controlled melt but - first - an ice gorge from upriver that compacted and upended large chunks of ice.

Those old wooden steamships trapped at Cincinnati and elsewhere up and down the Ohio River were gradually crushed. The damage to and the sinking of the City of Cincinnati side-wheeler was widely photographed;

While nature punished - perhaps righteously - the denizens of River City, beneficent favor graced the bucolic wooded hills and dales of northwest Butler County, Ohio.

The future was so bright for high school graduates they had to use parasols!

And just outside of Butler County, in the dark and untamed wilderness of Indiana, College Corner High School (above) managed a larger graduating class than Oxford in the spring of 1917. Deeper into the untamed wilds of nearby Indiana, the Liberty High School Class of 1917 (below) was twice as large as the O.H.S. Class of '17!

Such fine looking young ladies and gentlemen! Leads one to wonder how Indiana went downhill so fast afterward?

Athletics at Miami University flourished in 1917-1918. The Miami track and field team in 1917 looked like a swift and determined fleet (below);

Track and field upgraded to better uniforms for the 1918 season (below);

A similar jersey theme was employed by the Miami basketball team circa 1918;

Conference champs, baby!

The 1918 hoops team appeared to be more organized and certainly better uniformed than the 1917 team (below);

More research will need to be conducted in order to determine if 1918 was the beginning of uniform uniforms for Miami sports. Evidence suggests some validity to this theory. Even the American Rules Football team was not uniformly uniformed in 1918;

Western College fielded [sic] its own basketball team in 1918;

In the

This street fair scene purportedly dates from 1912, so a little cheating to include it here. That was back when the superior formula of Coca-Cola (excepting the cocaine ingredient, of course) today found only in the Mexican variant of Coca-Cola was the standard recipe everywhere.

The War to End all Wars came and went more fleetingly for Oxonians than it did for our European cousins, shattering that (probably mischaracterized) charmed and carefree existence forever.

The

Eagle-eyed readers will instantly recognize the photograph above as being the intersection of Main & High, Main St flanked by the East and West Park uptown. High St was brick by then but it appears as though Main St was still dirt. The buildings seen at far right, along the north side of High Street, stand to this day but the structures visible along the north side of East Park Place were long gone by the end of the 20th century. The cannon stood then in its original position before being moved to the West Park some 90 years later.

The ladies of Oxford marched along, too, carrying Old Glory!

A young man identified as William Robson, perhaps an Oxford resident or perhaps a Miami University student (or both) had his portrait taken in 1918 wearing his Army Air Corp uniform;

Also sitting for a photographic portrait in 1918 was an Oxford-area woman identified as Mable Earhart;

There may be no connection whatsoever, but generations of Oxford area youngsters familiar with the Legend of the Light, out on Oxford Milford Rd, would have by rote of tradition first turned around their cars in the driveway of the only residence - an old farmhouse - on Earhart Rd before performing the ensuing steps in the elaborate performance allegedly required in order to witness the oncoming headlight of the ghost motorcycle. I suspect there is some connection, however faint.

I'll leave you with this parting image, one of the earliest aerial photographs of Redland Field (later renamed Crosley Field), circa 1918;

The Oxford/Miami photographs were absconded with from the Miami University digital collection found here.

For more on the Ohio River ice gorge of 1918, visit this website.

Roll the credits!